DISCOGRAFIA

DISCOGRAFIA

NANA - Manfred Gurlitt

Opera in 4 atti su libretto di Max Brod

Enrico Calesso – maestro concertatore e direttore

Coro Theater Erfurt | Philharmonisches Orchester Erfurt

Produzione Theater Erfurt 2010

Con: Ilia Papandreou, Juri Batukov, Richard Carlucci, Erik Fenton, Vazgen Ghazaryan, Franziska Krötenheerdt, Julia Neumann, Peter Schöne, Máté Sólyom-Nagy, Dario Süß

World Premiere Recording – Etichetta: Delta Classics

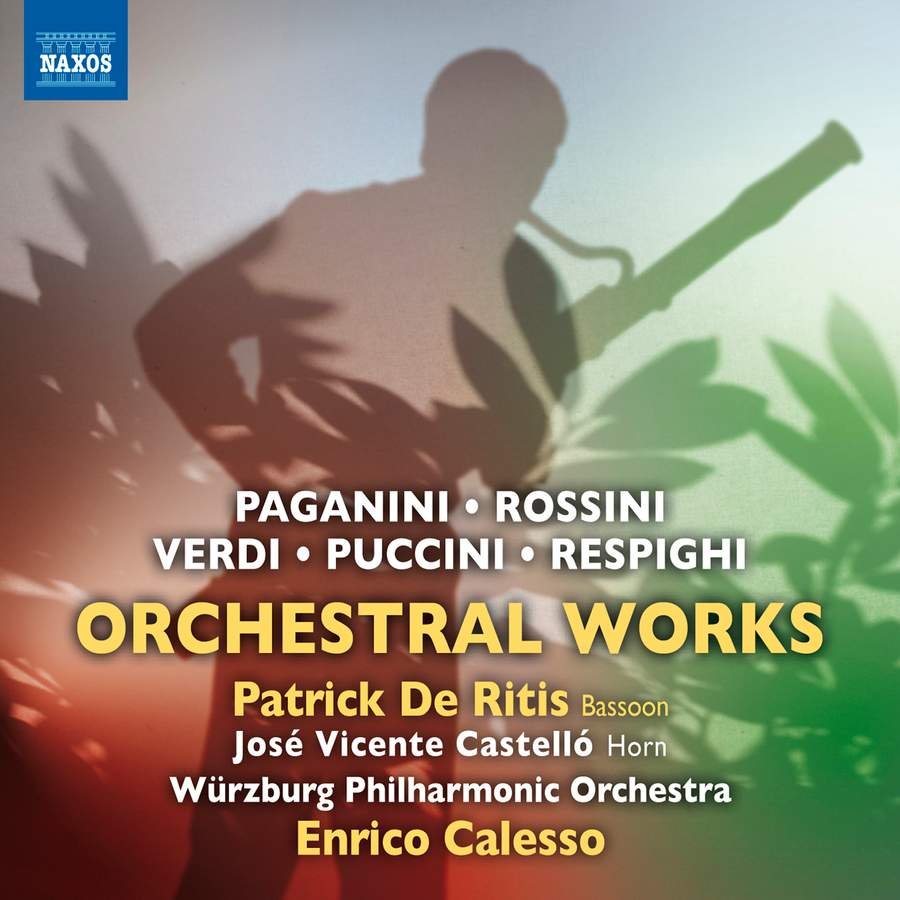

ORCHESTRAL WORKS (ITALIAN)

Giacomo Puccini, Preludio sinfonico

Gioachino Rossini, Concerto per fagotto e orchestra

Giuseppe Verdi, Capriccio per fagotto e orchestra

Niccolò Paganini, Concertino MS 65 per corno, fagotto ed orchestra

Ottorino Respighi, Suite da “La Boutique Fantasque”

Patrick De Ritis – fagotto | Jose Vicente Castello – corno

Enrico Calesso – direttore

Philharmonisches Orchester Würzburg

Live recording – Etichetta: Naxos

-

Critiche

Rob Maynard - MusicWeb International, April 2016:

All [pieces] feature the accomplished bassoonist Patrick De Ritis and he is joined in the Paganini by the equally talented and engaging horn-player José Vicente Castelló. …consistent pleasure is to be gained from Verdi’s capriccio, an engagingly rhythmic concoction that the young composer sensibly kept relatively succinct and to the point. The Paganini concertino is another well crafted piece and I was pleased to make its acquaintance in this attractive performance. The Würzburg orchestra’s accompaniment is consistently sensitive and appropriately scaled. Conductor Calesso ensures that everything from Verdi’s occasional passages of orchestral bel canto to the playful jauntiness of Rossini’s closing rondo emerges sharply focused and crystal clear. © 2016 MusicWeb International Read complete review

John Whitmore - MusicWeb International, February 2016:

Bassoon aficionados will snap this disc up, offering as it does a chance to hear some virtuoso pieces played with great authority and musicality by Patrick De Ritis, principal bassoonist with the Vienna Symphony Orchestra. Mr De Ritis also has a fine, rounded tone which suits the music admirably, especially in the higher register and during the legato passages.

Steven A. Kennedy - Cinemusical, February 2016:

…a good recording of a live performance showcasing an orchestra at its best. The Würzburg players are on fine display throughout these works providing great accompaniment to the bassoon works and getting a chance to shine more interpretively in the Respighi and Puccini pieces.

…a good recording of a live performance showcasing an orchestra at its best. The Würzburg players are on fine display throughout these works providing great accompaniment to the bassoon works and getting a chance to shine more interpretively in the Respighi and Puccini pieces. © 2016 Cinemusical Read complete review

Articolo di David Truslove

Giacomo Puccini (1858–1924): Preludio sinfonico

Born in Tuscany into a long line of church musicians, Giacomo Puccini first earned a living as an organist in his native Lucca. Although his name is almost exclusively associated with opera it was with small-scale orchestral works and sacred music that he first gained modest recognition. During his six years at Lucca’s Istituto Pacini his earliest compositions included what was to become known as the Messa di Gloria, a remarkably self-assured work that already exhibited considerable melodic gifts. In 1880, and supported by a small bursary, Puccini arrived at Milan’s Conservatory, (an institution that had once famously rejected Verdi) where the foundations of his future operatic achievements were cultivated. It was here that he produced one of his first significant orchestral essays, the Preludio sinfonico, a work as much an example of his own developing language as that of Wagner’s—whose music, despite its conspicuous absence from Milan’s two principal theatres, was becoming increasingly familiar to the city’s student population. At one of the Conservatory’s winter concerts Puccini could have heard a student performance of the Prelude to Die Meistersinger or Siegfried Idyll and by the time he composed his Preludio sinfonico in 1882 he was certainly familiar with the Prelude to Lohengrin.

The Preludio was first performed at a students’ concert in July and, despite its melodic invention and warmth of expression, drew a cool reception from the critic of Milan’s daily newspaper, La Perseveranza. Scored for full orchestra, and constructed around a single theme, the Preludio opens gently with the woodwind, echoed by the strings. Its veiled atmosphere soon lifts and builds towards an impassioned climax before gradually reaching a tender conclusion that bears some kinship with Lohengrin. In the craftsmanship of its orchestration and the Preludio’s surging passions one can already hear elements of his later operatic manner.

Gioachino Rossini (1792–1868): Bassoon Concerto

Like Puccini, Gioachino Rossini established himself through opera, and after two decades of unparalleled success in the genre he took early retirement (aged 37) and only in the late 1850s did he surrender his pre-eminent position in Italian operatic life. Aside from his stage works there are a handful of late choral works, numerous piano trifles and a magnificent setting of the Stabat Mater dating from 1841. It is to this decade when Rossini was a musical advisor to Bologna’s Liceo Musicale that the virtually unknown Bassoon Concerto belongs.

Although its authorship is unconfirmed, the concerto has been attributed to Rossini on the basis of an obituary published in 1893 for Nazzareno Gatti (a bassoon student at the Liceo during the 1840s) who claimed the composer had written the work for him. More recently a priest, Giuseppe Gregiati, discovered the concerto amongst a collection of nineteenth-century manuscripts in a library near Mantua and, despite its annotation by several hands, credited the concerto to Rossini. The concerto may have been written around 1845 as a “concerto da esperimento” (an examination concerto) for Nazzareno Gatti and performed by him for his final test at the Liceo.

The work is in three movements: the first, (Allegro) in B flat major, opens with an energetic orchestral paragraph prior to the bassoon’s first entry, a declamatory theme that soon generates more mellifluous material. Hushed pizzicato chords usher in a cantabile secondary theme, its graceful contours soon yielding to livelier figuration. While fresh ideas are explored and earlier material is refashioned, it is with the arrival of some nimble passage work (and the bassoon’s high D flat) that this movement provides an opportunity for dramatic display. In a dramatic shift to an unexpected shift to the key of C minor, the central Largo inhabits a Mozartian eloquence, its gentle theme culminating in a brief cadenza which leads directly to an ebullient Rondo. The change of metre and key (F major) underpins an infectious humour in a movement that poses considerable technical challenges. Even if the authenticity of this concerto is uncertain there is little doubt as to the work’s rhythmic impetus and melodic charm

Giuseppe Verdi (1813–1901): Capriccio for Bassoon and Orchestra

Unlike Rossini, whose parents were both musicians, there is little in Giuseppe Verdi’s immediate forbears to indicate musical potential. This “peasant from Roncole”, as he liked to call himself, was born into a family of small landowners and traders but from the age of nine he had become a church organist near the provincial town of Busseto, later beginning composition lessons there with Ferdinando Provesi. He became increasingly active in the town’s musical life, as organist and conductor, and as a composer he made his début with an alternative overture to Rossini’s Il barbiere di Siviglia.

After his rejection from Milan Conservatory Verdi pursued his musical studies privately and from 1836, took up appointments at Busseto’s church of San Bartolomeo and the Società Filarmonica. It is for this amateur orchestra that he composed a number of pièces d’occasion and, it is thought, the Capriccio for Bassoon and Orchestra. Many of the pieces written during this period were destroyed but this work and other manuscripts associated with Busseto resurfaced twenty years ago in the family archives of Cocchi-Cavalli. While there is no absolute certainty of Verdi composing this work, the American bassoonist James Kobb suggests in his comprehensive survey The Bassoon that the Capriccio “may be identical with a work for bassoon and orchestra performed in Busseto on 23 February 1838”

The Capriccio is in three parts: an extended Introduction, a set of Variations and a Coda. After a rousing tutti and a series of alternating phrases for bassoon and orchestra a stately theme unfolds; its noble temperament soon acquiring a more playful character. These two aspects combine and after a brief cadenza a closing tutti signals the Variation theme, outlined by the bassoon and accompanied by strings and horns. The ensuing variations, separated by orchestral ritornelli, bring melodic and rhythmic elaboration to the first two, a contrasting tempo and minor key in the third and a series of accelerandi in the fourth. Its carnival mood continues in the exhilarating closing section.

Niccolò Paganini (1782–1840): Concertino for Horn, Bassoon and Orchestra

Just as there was more to Verdi than opera so Nicolò Paganini demonstrated that he was far more than a violin virtuoso. His reputation as the greatest violinist of his age was secured after a series of recitals given in Vienna in 1828; thereafter, people flocked to hear him for the promise of his astonishing technique. Like many virtuosi of the time he performed his own compositions, and of these the 24 Caprices for Solo Violin (considered unplayable by many contemporaries) and six Violin Concertos are his most celebrated. Among his numerous other compositions there are several tribute pieces to Rossini (whose operas he admired), a handful of string quartets and this two-movement Concertino for Horn, Bassoon and Orchestra written around 1831, but not published until 1985.

Conceived for the renowned French bassoonist Antoine Nicholas Henry, the Concertino inhabits a classical sensitivity where fluency and elegance foreground virtuosic display. Its opening Larghetto is built on a dignified melody given out in turn by horn and bassoon, setting the stage for a series of graceful exchanges. The second of two climaxes heralds an Allegro moderato which presents a buoyant new theme (its initial rising contours derived from the earlier melody) coloured by unexpected harmonic progressions and vigorous tutti passages. An agile new idea from the bassoon provides playful contrast, before the horn reprises the buoyant theme and an extended coda brings this entertaining curiosity to an uplifting conclusion.

Ottorino Respighi (1879–1936): La boutique fantasque (Ballet after Rossini)

Nearly a century separates the birth of Paganini from Ottorino Respighi. He belonged to a generation of Italian composers who wished to revive interest in orchestral music (one of the glories of the Italian baroque) after a century of operatic domination. His own orchestral style evolved from personal study with Rimsky-Korsakov and a keen appreciation of Debussy, Ravel and Richard Strauss. This immersion later bore fruit in the first of his Roman trilogy tone poems, the Fountains of Rome of 1916 (Naxos 8.550529) which eventually brought Respighi international recognition thanks in part to the advocacy of Arturo Toscanini who had conducted a persuasive second performance of the work in 1918.

A year later in June 1919 his ballet music La boutique fantasque (The Enchanted Toy Shop) enjoyed a huge success at its première at London’s Alhambra theatre where The Times critic declared the audience “went off its head”. This triumph owes as much to Rossini as it does to Respighi, who had orchestrated a number of instrumental and vocal pieces by Rossini written during his last decade. Referred to as his Péchés de vieillesse (Sins of Old Age), these short pieces prompted Respighi to approach the impresario Sergey Dyagilev with an idea for a new stage work. Since Dyagilev had plans to revive a nineteenth-century ballet Die Puppenfee (The Enchanted Puppet) the resultant collaboration became La boutique fantasque.

The action takes place in a toy shop in 1860s Nice where an American and a Russian family come to look at the mechanical toys. They are shown various dolls, but are drawn to a pair of can-can dancers, and after a failed attempt to outbid one another, the dancers are sold separately. Packed and ready for collection the Shopkeeper closes up for the evening, but seeing the distress of the dancers the other toys come to the rescue and set them free. When the families return in the morning to discover their disappearance they turn on the Shopkeeper and the toys leap to his defence. The two families are then banished from the shop, and the can-can dancers reappear for the final dance.

This concert suite, made by Malcolm Sargent, gives us the essence of the score without the various linking passages, but in whichever form it is heard, it owes its success to the invention of Rossini’s originals and Respighi’s dazzling orchestrations.

David Truslove